Monday, July 23, 2012

RA Study Misses Primary Endpoint (CH-4051)...

Friday, September 20, 2013

Cell death protein could offer new anti-inflammatory drug target

Friday, August 11, 2017

New anti-inflammatory drug reduces death of existing brain cells then repairs damage after stroke

Researchers at The University of Manchester have discovered that a potential new drug reduces the number of brain cells destroyed by stroke and then helps to repair the damage.

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Podophyllotoxin in American Mayapple ?

Now the researchers from the US, found that mayapple colonies in the eastern part of the United States can be used for the development of high podophyllotoxin cultivars, which could subsequently provide the base for commercial production of podophyllotoxin in the United States.

Ref : http://hortsci.ashspublications.org/cgi/content/abstract/44/2/349

Monday, January 11, 2021

FDA Issues EUA to Baricitinib Plus Remdesivir for COVID-19

In continuation of my update on baricitinib and remdesivir

Emergency use authorization was issued for baricitinib in combination with remdesivir for hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced Thursday.

The EUA for the combination treatment applies to hospitalized patients ages 2 years and older with suspected or laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 who require supplemental oxygen, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib is currently FDA-approved for treating moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis.

Based on the agency's review of the evidence, the FDA "determined that it is reasonable to believe that baricitinib, in combination with remdesivir, may be effective in treating COVID-19 for the authorized population. And, when used under the conditions described in the EUA to treat COVID-19, the known and potential benefits of baricitinib outweigh the known and potential risks for the drug."

The FDA granted the EUA based on data from the ACTT-2 trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The trial included 1,033 patients -- 515 randomly assigned to baricitinib plus remdesivir and 518 randomly assigned to placebo plus remdesivir. Patients were followed for 29 days. Median time to recovery from COVID-19 was seven and eight days for patients receiving baricitinib plus remdesivir and those receiving placebo plus remdesivir, respectively. Patients receiving baricitinib plus remdesivir had significantly lower odds of progressing to death or being ventilated at 29 days and significantly higher odds of clinical improvement at 15 days compared with patients receiving placebo plus remdesivir.

Baricitinib is not authorized or approved as a stand-alone treatment for COVID-19, the FDA notes. Its safety and effectiveness for use in the treatment of COVID-19 continue to be evaluated.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baricitinib

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remdesivir

Tuesday, February 26, 2019

Rituximab (Rituxan) May Delay MS Disability

"This is a potentially valuable treatment, but there are still a lot of questions. Other studies are underway looking at the value of rituximab," LaRocca said.

Monday, May 22, 2017

Drugs designed to target nervous system could control inflammation in the gut, study shows

"We are talking about an existing set of drugs and drug targets that could open up the spectrum of potential therapeutic applications by targeting pathways that fine-tune the inflammatory response," said Alejandro Aballay, Ph.D., a professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke School of Medicine.

"Worms have evolved mechanisms to deal with colonizing bacteria," Aballay said. "That is true for us as well. Humans have trillions of microorganisms in our guts, and we have to be careful when activating antimicrobial defenses so that we mainly target potentially harmful microbes, without damaging our good bacteria -- or even our own cells -- in the process."

Friday, July 6, 2012

A high-throughput drug screen for Entamoeba histolytica identifies a new lead and target

Thursday, July 23, 2015

Effimune obtains regulatory approval for Phase I clinical trial in humans of its new immunomodulator FR104

Benzoic acid, 2,3,4,5-tetrachloro-6-(2, 4,5,7-tetrabromo-6-hydroxy-3-oxo-3H-xanthen-9-yl) -

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Minocycline for stroke patients?

A recent study by the Dr. Cesar V. Borlongan (University of South Florida, USA) has lead to some interesting result, i.e., minocycline can be used to treat the stroke patients !. As per the claim by the researchers this drug might be a better option, when compared with the thrombolytic agent tPA (the only effective drug for acute ischemic stroke) and more over only 2 % of ischemic stroke patients benefit from this treatment due to its limited therapeutic window.

During a stroke, a clot prevents blood flow to parts of the brain, which can have wide ranging short-term and long-term implications. This study recorded the effect of intravenous minocycline in both isolated neurons and animal models after a stroke had been experimentally induced. At low doses it was found to have a neuroprotective effect on neurons by reducing apoptosis of neuronal cells and ameliorating behavioral deficits caused by stroke. The safety and therapeutic efficacy of low dose minocycline and its robust neuroprotective effects during acute ischemic stroke make it an appealing drug candidate for stroke therapy claims the researchers. Congrats for this interesting finding...

Ref : http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2202/10/126/abstract

Saturday, May 8, 2010

Vinpocetine from the periwinkle plant, as a potent anti-inflammatory agent....

"Given vinpocetine's efficacy and solid safety profile, we believe there is great potential to bring this drug to market." claims co-author, Dr. Bradford C. Berk...

Inflammatory diseases are a major cause of illness worldwide. For example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States. In people with COPD, airflow is blocked due to chronic bronchitis or emphysema, making it increasingly difficult to breathe. Most COPD is caused by long-term smoking, although genetics may play a role as well.....

Ref : http://www.urmc.rochester.edu/news/story/index.cfm?id=2836

Monday, April 26, 2010

MIF (Macrophage migration Inhibitory Factor) - a new molecular target for the treatment of depressant and anxiety...

Friday, November 13, 2015

Research finding offers hope for more powerful aspirin-like drugs

Friday, May 27, 2011

Gout drug success for Novartis

Gout drug success for Novartis

Friday, December 20, 2013

Repurposed drug may be first targeted treatment for serious kidney disease

Sunday, April 11, 2010

Minocycline - Effective defense against HIV ?

Wednesday, August 8, 2018

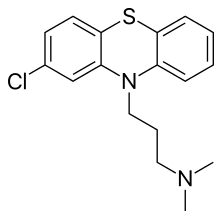

Drugs that suppress immune system may protect against Parkinson's

"The idea that a person's immune system could be contributing to neurologic damage has been suggested for quite some time," said Brad Racette, MD, the Robert Allan Finke Professor of Neurology and the study's senior author. "We've found that taking certain classes of immunosuppressant drugs reduces the risk of developing Parkinson's. One group of drugs in particular looks really promising and warrants further investigation to determine whether it can slow disease progression."

"What we really need is a drug for people who are newly diagnosed, to prevent the disease from worsening," Racette said. "It's a reasonable assumption that if a drug reduces the risk of getting Parkinson's, it also will slow disease progression, and we're exploring that now."

"Our next step is to conduct a proof-of-concept study with people newly diagnosed with Parkinson's disease to see whether these drugs have the effect on the immune system that we'd expect," Racette said. "It's too early to be thinking about clinical trials to see whether it modifies the disease, but the potential is intriguing."