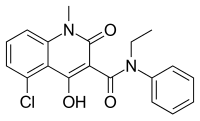

The experimental drug laquinimod may prevent the development or reduce the progression of multiple sclerosis (MS) in mice, according to research published in the September 21, 2016, online issue of Neurology® Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation, a medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

"These results are promising because they provide hope for people with progressive MS, an advanced version of the disease for which there is currently no treatment," said study author Scott Zamvil, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco and a Fellow of the American Academy of Neurology.

In a proper immune response, T cells and B cells help the body develop immunity to prevent infection. But in MS, an immune and neurodegenerative disorder, those cells can help create antibodies that attack and destroy myelin, the protective, fatty sheath that insulates nerves in the brain and spinal cord.

For this research, the investigators studied mice that develop a spontaneous form of MS. Mice were either given daily oral laquinimod or a placebo (water). The number of T cells and B cells were then examined.

In one study of 50 mice, only 29 percent of the mice given oral laquinimod developed MS as opposed to 58 percent of the mice given the placebo, evidence the drug may prevent MS. Plus, there was a 96-percent reduction in harmful clusters of B cells called meningeal B cell aggregates. In people, such clusters are found only in those with progressive MS.

In a second study of 22 mice, researchers gave laquinimod after mice developed paralysis and observed a reduction in progression of the disease. When compared to the control, mice given the drug showed a 49-percent reduction in dendritic cells that help create special T cells called T follicular helper cells, a 46-percent reduction in those T cells and a 60-percent reduction in harmful antibodies.

"This study has given us more insight into how laquinimod works," Zamvil said. "But because this was an animal study, more research needs to be done before we know if it could have similar results in people."

Midostaurin

Midostaurin