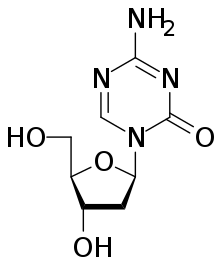

Guadecitabine works to reverse a so-called epigenetic change in cancer cells known as methylation, which may alter genetic activity in cells in a way that can block the action of tumor-suppressing genes, pushing cells to become cancerous and resistant to therapy. By reversing this change in cancer cells, the drug restores cancer cells' vulnerability to drugs such as irinotecan.

The clinical trial included 22 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who had been treated previously with irinotecan and whose disease was progressing. The patients were divided into four groups, each receiving different doses of guadecitabine in combination with irinotecan, over an average period of four months.

During the study, 15 patients had at least one imaging scan to retest the extent and location of their cancers -- with 12 patients experiencing stable disease -- for more than the four-month period, on average, and one patient experiencing a partial response to the treatment (measured as at least a 30 percent reduction in the size of the tumors.)

Although the study's main purpose was to test the safety rather than the effectiveness of guadecitabine doses, "we were very happy to see some patients who benefited from the combination of the therapies for many months to more than a year," says Nilofer Azad, M.D., professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The study also showed signs that guadecitabine reduced methylation among the cancer cells. "We did see that giving a higher dose of the drug seemed to produce a better methylation response among patients," says Valerie Lee, M.D., a fellow at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center. "However, it seemed that patients were responding at all levels of the drug."

Among the side effects of the combined treatment, 16 patients experienced neutropenia, a low count of the infection-fighting white blood cells called neutrophils; five patients with neutropenia had fevers; three patients became anemic; and two patients developed thrombocytopenia, a lowered count of blood-clotting platelets. Other side effects included diarrhea (three patients), fatigue (two patients) and dehydration (two patients). There was one death during the study, possibly resulting from febrile neutropenia caused by the treatment.

The current study was based on previous studies in the laboratory of Nita Ahuja, M.D., director of the Sarcoma and Peritoneal Surface Malignancy Program and professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, which showed that guadecitabine limited the growth of colorectal cancer cell lines when combined with irinotecan, says Azad.

The drug combination is being tested in an ongoing phase II clinical trial (NCT01896856) in a larger group of metastatic colorectal cancer patients at multiple institutions to determine the effectiveness of the dual therapy compared with chemotherapy regimens that do not include guadecitabine, says Azad.

Scientists leading the new study will also look for biomarkers in patients that could help determine which of them are most likely to benefit from guadecitabine and irinotecan. Lee says the research team will measure the amount of methylation in patients' cells when they begin their treatment and the presence of genes associated with irinotecan resistance, among other possible biomarkers.

In 2015, there were more than 130,000 people in the U.S. diagnosed with colon cancers. Five-year survival rates among people with localized colon cancers are more than 90 percent, but they are only 20 percent in those with metastatic cancer.

Guadecitabine is an experimental drug that has not been approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It is manufactured by Astex Pharmaceuticals, a supporter of the Johns Hopkins-led study. The research was also supported by the Van Andel Research Institute SU2C/AACR Epigenetics Dream Team.

Other scientists who contributed to the research include Judy Wang, Anup Sharma, Zachary Kerner, Stephen Baylin, Ellen Lilly, and Thomas Brown from Johns Hopkins; Anthony El Khoueiry from the University of Southern California; Henk Verheul and Elske Gootjes from Vrije Universiteit in the Netherlands; and Peter Jones from the Van Andel Research Institute.