Saturday, August 27, 2016

Friday, August 26, 2016

Existing non-antibiotic therapeutic drugs could help combat antibiotic-resistant pathogens

The rise of antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens is an increasingly global threat to public health. In the United States alone antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens kill thousands every year.

But non-antibiotic therapeutic drugs already approved for other purposes in people could be effective in fighting the antibiotic-resistant pathogens, according to a new study from researchers at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Antibiotic resistance is increasing due to the over prescription of antibiotics, said Ashok Chopra, a professor at UTMB and author of the new study in the Journal of Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. But the solution could lie with drugs originally meant for other uses that, until now, no one knew could also help combat bacterial infections.

While antibiotics have been highly effective at treating infectious diseases, infectious bacteria have adapted to them and antibiotics have become less effective, according to the Centers for disease Control and Prevention. About 2 million people in the United States are infected with antibiotic resistant bacteria every year and at least 23,000 die, according to the CDC.

"There are no new antibiotics which are being developed and nobody really has given much emphasis to this because everyone feels we have enough antibiotics in the market," Chopra said. "But now the problem is that bugs are becoming resistant to multiple antibiotics. That's why we started thinking about looking at other molecules that could have some effect in killing such antibiotic resistant bacteria."

By screening a library of 780 Food and Drug Administration approved therapeutics, Chopra, Jourdan Andersson, a graduate student at UTMB, and others on the research team were able to identify as many as 94 drugs that were significantly effective in a cell-culture system when tested against Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that cause the plague and which is becoming antibiotic resistant.

After further screening, three drugs, trifluoperazine, an antipsychotic, doxapram, a breathing stimulant, and amoxapine, an anti-depressant, were used in a mouse model and were found to be effective in treating plague. In further experiments, trifluoperazine was successfully used to treat Salmonella enterica and Clostridium difficile infections, both of which are listed as drug-resistant bacteria of serious threat by the CDC.

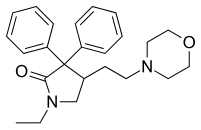

Amoxapine

Amoxapine  Doxapram hydrochloride

Doxapram hydrochloride Trifluoperazine

Trifluoperazine

"It is quite possible these drugs are already, unknowingly, treating infections when prescribed for other reasons," Chopra said.

Since these are not antibiotics these drugs are not attacking the bacteria. Instead, they could be dealing with these bacteria in a couple of different ways, Chopra said.

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

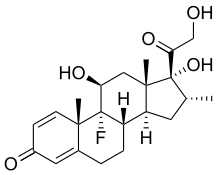

One-dose of dexamethasone can improve outcomes of asthmatic patients in ER

In continuation of my update on dexamethasone

Adults with asthma who were treated with one-dose dexamethasone in the emergency department had only slightly higher relapse than patients who were treated with a 5-day course of prednisone. "Enhanced compliance and convenience may support the use of dexamethasone" is the conclusion of a study that was published online Friday inAnnals of Emergency Medicine ("A Randomized Controlled Noninferiority Trial of Single Dose vs. Five Days of Oral Dexamethasone in Acute Adult Asthma").

"Any time we can reduce the role of patient compliance with asthma, we have a chance of improving outcomes," said lead study author Matthew W. Rehrer, MD, of the Department of Emergency Medicine with Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif. "Dexamethasone allows the emergency physician to administer treatment in one dose and doesn't rely on the patient to remember to take her pills for four more days after leaving the ER. A single dose of medication eliminates prescription adherence barriers such as forgetfulness, cost and dose omission."

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

Experimental drug cancels effect from key intellectual disability gene in mice.

A University of Wisconsin-Madison researcher who studies the most common genetic intellectual disability has used an experimental drug to reverse -- in mice -- damage from the mutation that causes the syndrome.

The condition, called fragile X, has devastating effects on intellectual abilities.

Fragile X affects one boy in 4,000 and one girl in 7,000. It is caused by a mutation in a gene that fails to make the protein FMRP. In 2011, Xinyu Zhao, a professor of neuroscience, showed that deleting the gene that makes FMRP in a region of the brain that is essential to memory formation caused memory deficits in mice that mirror human fragile X.

The deletions specifically affected neural stem cells and the new neurons that they form in the hippocampus.

Tantalizingly, Zhao's 2011 study showed that reactivating production of FMRP in new neurons could restore the formation of new memories in the mice. But what remained unclear was exactly how the absence of FMRP was blocking neuron formation, and whether there was any practical way to avert the resulting disability.

Now, in a study published on April 27 in Science Translational Medicine, Zhao and her colleagues at the Waisman Center at UW-Madison have detailed new steps in the complex chain reaction that starts with the loss of FMRP and ends up with mice that cannot remember what they had recently been sniffing.

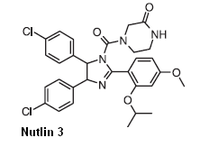

This study's newfound understanding of the biochemical chain of events became the basis for identifying an experimental cancer drug called Nutlin-3, which blocks the reaction.

In the new study, mice with the FMRP deletion took Nutlin-3 for two weeks. When tested four weeks later, they regained the ability to remember what they had seen -- and smelled -- in their first visit to a test chamber.

Statistically, the memory capacities of normal mice and fragile X models that were treated with Nutlin-3 were identical.

Still, many hurdles remain before the advance can be tested on human patients, Zhao says. "We are a long way from declaring a cure for fragile X, but these results are promising."

Fragile X appears after birth, says Zhao. "Parents start to notice something is wrong, but even if they get an accurate diagnosis, there is no treatment at present. I'm encouraged because affecting this gene's pathway does seem to reverse the memory impairment."

The mouse memory test relied on curiosity. "We placed two objects in an enclosure and let the mice run around," Zhao says. "Mice are naturally curious, so they explore and sniff each one. We take them out after 10 minutes, replace one object with a different one, wait 24 hours and put the mouse back in. If the mouse has normal learning ability, it will recognize the new object and spend more time with it. Mice without the FMRP gene don't remember the old object, so they spend a similar amount of time on each one."

The behavioral assessment was done by different people, says Zhao. "First author Yue Li, a postdoctoral researcher at Waisman, ran the test and sent the video to Michael Stockton, an undergraduate working on the project." Stockton timed how and where each mouse was exploring, "but he had no idea which mouse was which," Zhao says. "It was fantastic to see such clear data."

Two other undergraduates, Jessica Miller and Ismat Bhuiyan (who is now in graduate school) and postdoctoral fellows Brian Eisinger and Yu Gao also worked on the study. The Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation has applied for a patent on the discovery.

Nutlin-3, which can block the last stage of the chain reaction set off by a mutation in the FMRP gene, is in phase 1 trial for the treatment of the eye cancer retinoblastoma. Finding a new use for a drug that is approved, or that like Nutlin-3 and several derivatives, has entered the approval process, may shorten the lengthy FDA process, says Zhao.

The dose used in the trial -- only 10 percent of the dose proposed for cancer chemotherapy -- caused no apparent harm, she says. "We measured body weight and activity. So far, the mice look healthy and happy."

Because more than one-third of fragile X patients are also diagnosed with autism, the study may shed light on that condition.

In any case, it's far too soon to declare victory over fragile X, Zhao stresses. "There are many hurdles. Among the many questions that need to be answered is how often the treatment would be needed. Still, we've drawn back the curtain on fragile X a bit, and that makes me optimistic."

Monday, August 22, 2016

New molecule-building method may have great impact on pharmaceutical industry

Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have devised a new molecule-building method that is likely to have a major impact on the pharmaceutical industry and many other chemistry-based enterprises.

The method, published as an online First Release paper in Science on April 21, 2016, allows chemists to construct novel, complex and potentially very valuable molecules, starting from a large class of compounds known as carboxylic acids, which are relatively cheap and non-toxic. Carboxylic acids include the amino acids that make proteins, fatty acids found in animals and plants, citric acid, acetic acid (vinegar) and many other substances that are already produced in industrial quantities.

"This is one of the most useful methods we have ever worked with, and it mostly involves materials that every chemist has access to already, so I think the interest in it will expand rapidly," said principal investigator Phil S. Baran, Darlene Shiley Professor of Chemistry at TSRI.

"This exciting new discovery represents a significant advance in our ability to transform simple organic molecules and to rapidly build complex structures from readily available materials—we expect to use it in both the discovery and development of biologically active compounds that help patients prevail over serious disease," said co-author Martin D. Eastgate, a Director in Chemical and Synthetic Development at Bristol-Myers Squibb, who participated in the study as part of a long-standing research collaboration between Bristol-Myers Squibb and TSRI.

The new method is a modification of what is already one of the most widely used sets of chemical reactions: amide bond-forming reactions. These occur naturally in cells to stitch together amino-acids into proteins, for example. Since the 1940s, when they became a popular tool for laboratory chemists, they have been instrumental in the discovery of many new compounds as well as new methods for synthesizing compounds.

Amide bond-forming reactions couple carbon atoms on carboxylic acids to nitrogen atoms on another broad class of compounds called amines. The reactions are relatively safe and easy, and produce water, H2O, as a co-product. Chemists have long dreamed of using similarly cheap and easy techniques to make carbon-to-carbon couplings. That would enable them to synthesize, and potentially turn into drugs and other useful products, an enormous number of organic molecules that have previously been inaccessible.

Carbon to Carbon

The method devised by Baran and his team essentially repurposes the traditional amide bond-forming strategy to achieve carbon-carbon couplings. The new reactions again involve easy, safe conditions—the co-product now is carbon dioxide, CO2—and the same inexpensive and widely available starting materials, carboxylic acids. This time the reaction partners are not nitrogen-containing amines but organic compounds containing carbon and zinc, which are also relatively easy to buy or make.

The path to the new invention began with a long-known reaction called the Barton decarboxylation. "We started by asking ourselves what would happen if we could use a metal to trap a radical [a highly reactive charged molecule] generated in the Barton decarboxylation," said TSRI Research Associate Josep Cornella. "We realized that if we could do that, it would open up a totally new approach to organic synthesis and carbon-carbon coupling."

The method the team ultimately developed employs an inexpensive and commercially available activating agent that primes the chosen carboxylic acid for the reaction. A metal catalyst—inexpensive nickel—then facilitates the reaction between the carboxylic acid and its carbon-zinc partner compound.

A key ingredient turned out to be a "ligand" compound that helps the metal catalyst do its job. "We found that common, readily available bipyridine ligands work best—these help to stabilize the nickel so it can catalyze the reaction," said TSRI Research Associate Tian Qin.

Friday, August 19, 2016

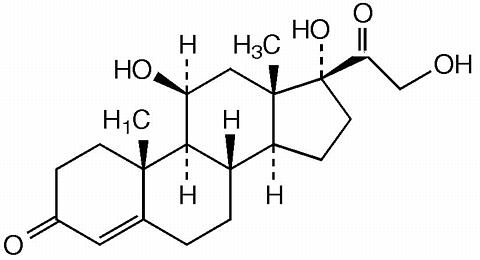

Hydrocortisone drug can also prevent lung damage in premature babies

Research from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago conducted in mice shows the drug hydrocortisone a steroid commonly used to treat a variety of inflammatory and allergic conditions -- can also prevent lung damage that often develops in premature babies treated with oxygen.

If affirmed in human studies, the results could help pave the way to a much-needed therapy for a bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a condition that affects 10,000 newborns in the United States each year and can lead to chronic lung disease and, ultimately, heart failure. In a set of experiments, to be published in the May print issue of the journal Pediatric Research, a team of Lurie Children's scientists showed the drug reduced damage to the delicate blood vessels inside the lungs of newborn mice and reversed some of BPD's harmful downstream effects on the heart.

"Bronchopulmonary dysplasia is a devastating, often unavoidable side effect of a standard lifesaving therapy with oxygen used to treat newborn babies, so our findings are a promising indicator that a well-known drug that's been around for a long time may help stave off some of this condition's worst after-effects," says study lead investigator and Lurie Children's neonatologist Marta Perez, M.D., who is also assistant professor of Pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Thursday, August 18, 2016

Soy shows promise as natural anti-microbial agent

In continuation of my update on soy

Soy isoflavones and peptides may inhibit the growth of microbial pathogens that cause food-borne illnesses, according to a new study from University of Guelph researchers.

Soybean derivatives are already a mainstay in food products, such as cooking oils, cheeses, ice cream, margarine, food spreads, canned foods and baked goods.

The use of soy isoflavones and peptides to reduce microbial contamination could benefit the food industry, which currently uses synthetic additives to protect foods, says engineering professor Suresh Neethirajan, director of the BioNano Laboratory.

U of G researchers used microfluidics and high-throughput screening to run millions of tests in a short period.

They found that soy can be a more effective antimicrobial agent than the current roster of synthetic chemicals.

The study is set to be published in the journal Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports this summer and is available online now.

"Heavy use of chemical antimicrobial agents has caused some strains of bacteria to become very resistant to them, rendering them ineffective for the most part," said Neethirajan.

"Soy peptides and isoflavones are biodegradable, environmentally friendly and non-toxic. The demand for new ways to combat microbes is huge, and our study suggests soy-based isoflavones and peptides could be part of the solution."

Neethirajan and his team found soy peptides and isoflavones limited growth of some bacteria, including Listeria and Pseudomonas pathogens.

"The really exciting thing about this study is that it shows promise in overcoming the issue of current antibiotics killing bacteria indiscriminately, whether they are pathogenic or beneficial. You need beneficial bacteria in your intestines to be able to properly process food," he said.

Peptides are part of proteins, and can act as hormones, hormone producers or neurotransmitters. Isoflavones act as hormones and control much of the biological activity on the cellular level.

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

New drug combination before surgery may improve outcomes in breast cancer patients

In continuation of my update on Paclitaxel

Results from the I-SPY 2 trial show that giving patients with HER2-positive invasive breast cancer a combination of the drugs trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and pertuzumab before surgery was more beneficial than the combination of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab. Previous studies have shown that a combination of T-DM1 and pertuzumab is safe and effective against advanced, metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer, but in the new results, investigators tested whether the combination would also be effective if given earlier in the course of treatment. Results of the study are presented by trial investigators from the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania at the AACR Annual Meeting 2016, April 16-20.

In this latest phase of the I-SPY2 trial, investigators worked to determine whether T-DM1 plus pertuzumab could eradicate residual disease (known as pathological complete response, or pCR) for more patients if delivered before surgery to shrink cancer tumors compared with paclitaxel plus trastuzumab. They also examined whether this combination could meet that goal without the need for patients to receive paclitaxel.

"The combination of T-DM1 and pertuzumab substantially reduced the amount of residual disease in the breast tissue and lymph nodes for all subgroups of HER2-positive breast cancers compared with those in the control group," said lead author, Angela DeMichele, MD, MSCE, a professor of Medicine and Epidemiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, who will present the findings. "Our results suggest a possible new treatment option for patients that can not only effectively shrink tumors in the breast, but potentially reduce the chance of the cancer coming back later. The results also show that by replacing older, non-targeted therapies with more effective and less-toxic new therapies, we have the potential to both improve outcomes and decrease side effects."

For the study, patients whose tumors were 2.5 cm or bigger were randomly assigned to 12 weekly cycles of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab (control) or T-DM1 plus pertuzumab (test). Following the initial test period, all patients received four cycles of the chemotherapies doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, and surgery. Patients' tumors were then tested for one of three biomarker signatures: HER2-positive, HER2-positive and hormone receptor (HR)-positive, and HER2-positive and HR-negative.

New drug combination before surgery may improve outcomes in breast cancer patients: Results from the I-SPY 2 trial show that giving patients with HER2-positive invasive breast cancer a combination of the drugs trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and pertuzumab before surgery was more beneficial than the combination of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab.

Labels:

HER2-positive,

paclitaxel,

Pertuzumab

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

New clinical study to evaluate inexpensive drug to prevent type 1 diabetes

In continuation of my update on metformin

New trial aims to prevent type 1 diabetes

A clinical study evaluating a new hypothesis that an inexpensive drug with a simple treatment regimen can prevent type 1 diabetes will be launched in Dundee tomorrow.

The autoimmune diabetes Accelerator Prevention Trial (adAPT) is led by Professor Terence Wilkin, of the University of Exeter Medical School, with support from colleagues at the University of Dundee and NHS Tayside. It will be launched at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, on Tuesday, 19th April.

Initial funding of $1.7 million is being provided by JDRF, the leading global organisation backing type 1 diabetes research. The study aims to contact all 6,400 families in Scotland affected by the condition, with a view to expanding into England at a later date. Children aged 5 to 16 who have a sibling or parent with type 1 diabetes will be invited for a blood test to establish whether they are at high risk of developing the disease. If so, they will be invited to take part in the trial.

Researchers will then examine the impact of administering metformin, the world's most commonly prescribed diabetes medicine, to young people in the high-risk category. If successful, the large-scale trial could explain why the incidence of type 1 diabetes has risen five-fold in the last 40 years, and provide a means of preventing it.

Researchers have previously hypothesised that type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease caused by a faulty immune system which attacks and destroys insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Clinical trials have tried drugs that supress the immune system to attempt to subdue the attack, but the results have so far been disappointing.

The Accelerator Prevention Trial is the first to test an alternative explanation for type 1 diabetes, and is based on the accelerator hypothesis, proposed in 2001 by Professor Wilkin.

This hypothesis theorises that autoimmunity occurs as a response to damaged beta cells. It believes that beta cells, stressed by being made to work too hard in a modern environment, send out signals that switch on the immune system. adAPT will test whether metformin, which is known to protect the beta cells from stress, can stop the immune response that goes on to destroy them.

Professor Wilkin said, "We still have no means of preventing type 1 diabetes, which, at all ages, results from insufficient insulin. We all lose beta cells over the course of our lives, but most of us have enough for normal function.

"However, if the rate of beta cell loss is accelerated, type 1 diabetes develops, and the faster the loss, the younger the onset of the condition. The accelerator hypothesis talks of fast and slow type 1 diabetes - beta cell loss which progresses at different rates in different people, and appears at different ages as a result."

Monday, August 15, 2016

Experimental treatment shrinks rare pediatric tumor by 90%

When a baby's life was threatened by a rare pediatric cancer that would not respond to surgery or chemotherapy, doctors at Nemours Children's Hospital rapidly, successfully shrank the tumor by 90 percent using an experimental treatment, according to a new study published online in Pediatric Blood and Cancer. The now-20-month-old girl achieved the remarkable improvement by receiving a drug called LOXO-101 that was being tested on adults, researchers reported.

"Most infants and children with infantile fibrosarcoma (IFS) can be cured through surgery and chemotherapy. When our patient's disease progressed in spite of these treatments, we had to investigate new options that could target the disease," said Dr. Ramamoorthy Nagasubramanian M.D., lead author of the manuscript, division chief of pediatric hematology-oncology at Nemours Children's Hospital. "The dramatic reduction in tumor size shows early but promising evidence of the potential for LOXO-101 to provide significant benefit for pediatric patients with NTRK gene fusions."

Nemours' oncology team operated on the girl at 6 months to remove a large tumor located in the neck and face. The tumor did not respond to standard chemotherapy and relapsed after extensive surgery. Genetic testing confirmed an ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion, which is frequently found in IFS. At the time, LOXO-101 was in a Phase 1 multi-center basket trial in adults. Working with Nemours, Loxo Oncology, Inc., a biopharmaceutical company developing highly selective medicines for patients with genetically defined cancers, was able to expand the trial to children and enroll her.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)